Dr. Thomas Boyce, an emeritus professor of pediatrics and psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, has treated children who seem to be completely unflappable and unfazed by their surroundings — as well as those who are extremely sensitive to their environments. Over the years, he began to liken these two types of children to two very different flowers: dandelions and orchids.

Broadly speaking, says Boyce — who also has spent nearly 40 years studying the human stress response, especially in children — most kids tend to be like dandelions, fairly resilient and able to cope with stress and adversity in their lives. But a minority of kids, those he calls “orchid children,” are more sensitive and biologically reactive to their circumstances, which makes it harder for them to deal with stressful situations.

Get the latest news Boston is talking about sent to your inbox each day. Subscribe here.

Like the flower, Boyce says, “the orchid child is the child who shows great sensitivity and susceptibility to both bad and good environments in which he or she finds herself or himself.”

Given supportive, nurturing conditions, orchid children can thrive — especially, Boyce says, if they have the comfort of a regular routine.

“Orchid children seem to thrive on having things like dinner every night in the same place at the same time with the same people, having certain kinds of rituals that the family goes through week to week, month to month,” he says. “This kind of routine and sameness of life from day to day, week to week, seems to be something that is helpful to kids with these great susceptibilities.”

Boyce’s new book is The Orchid and the Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle and How All Can Thrive.

Interview highlights:

On the lab test he did to determine if a child is an orchid or a dandelion

We made an effort to try to understand these individual differences between children in how they respond biologically to mild, common kinds of challenges and stressors, and the way we did that was we brought them into a laboratory setting. We sat them down in front of an examiner — a research assistant that they had not previously met — and we asked them to go through a series of mildly challenging tasks. These were things like recounting a series of digits that the examiner asked them to say and increasing that from first three to four to five digits; having them just engage in a conversation with this examiner, who might ask them about their birthday or presents or something about their family. That, in itself, is a challenge for a young child. Putting a drop of lemon juice on the tongue was another kind of challenge that was evocative of these changes in biological response. …

We measured their stress response using the two primary stress response systems in the human brain. [One was] the cortisol system, which is centered in the hypothalamus of the brain. This is the system that releases the stress hormone cortisol, which has profound effects on both immune function and cardiovascular functioning.

And then the second stress response system is the autonomic nervous system, or the “fight-or-flight” system. This is the one that is responsible for the sweaty palms and a little bit of tremulousness, the dilation of the pupils, all of these things that we associate with the fight-or-flight response. So we were monitoring responsivity and both of those systems as the children went through these mildly challenging tasks. …

We found that there were huge differences [among] children. There were some children at the high end of the spectrum, who had dramatic reactivity in both the cortisol system and the fight-or-flight system, and there were other children who had almost no biological response to the challenges that we presented to them.

On how a child’s responsivity to stressors can be connected to physical and emotional behavioral outcomes

We find in our research that the same kinds of patterns of response are found for both physical illnesses, like severe respiratory disease, pneumonia, asthma and so on, as well as or more [in] emotional behavioral outcomes, like anxiety and depression and externalizing kinds of symptoms. So we believe that the same patterns of susceptibility that we find in the orchid child versus the dandelion child work themselves out not only for physical ailments but also for psychosocial and emotional problems. And we believe that the same kinds of underlying biological processes work for both. …

We do know, for example, that these two stress response systems … the cortisol system and the fight-or-flight system, the autonomic nervous system, both of those have powerful effects on the immune system, so they can alter the child’s ability to build an immune defense against viruses and bacteria that he or she may be exposed to. And they have also powerful effects on the cardiovascular system, so [they] could eventually, in adult life, predispose to developing hypertension, high blood pressure or other kinds of cardiovascular risk.

On how children’s experiences can vary, even within the same family

The experience of children within a given family, the siblings within a family — although they are being reared with the same parents in the same house in the same neighborhood — they actually have quite different kinds of experiences that depend upon the birth order of the child, the gender of the child, to some extent differences in genetic sequence. It is a way of talking about these dramatic differences that kids from different birth orders and different genders have within a given family.

On pushing orchid kids to stretch to do new or difficult things

I think that this is probably the most difficult parenting task in raising an orchid child. The parent of an orchid child needs to walk this very fine line between, on the one hand, not pushing them into circumstances that are really going to overwhelm them and make them greatly fearful, but, on the other hand, not protecting them so much that they don’t have experiences of mastery of these kinds of fearful situations.

Sam Briger and Seth Kelley produced and edited the audio of this interview. Bridget Bentz and Molly Seavy-Nesper adapted it for the Web.

Copyright NPR 2019.9(MDAyNzUwMDI2MDEyNTA3MTU5NzcyNTQyNA004))

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Dave Davies in for Terry Gross. When parents talk with other parents about their children, it’s common to hear them remark on how different two kids can be born just a couple of years apart and reared in the same family. Our guest Dr. Thomas Boyce says there’s plenty of research, some of it his own, to support that notion. Broadly speaking, he says most children are resilient, able to cope pretty well with stress and adversity in their lives. But a minority of kids are more sensitive and biologically reactive to their circumstances, which makes it harder for them to deal with stressful situations.

In his new book, he says he picked up the name for the two types from an elderly Swedish man, who attended a lecture of his, who said the resilient ones are dandelion children ready to thrive in any soil. The others Boyce calls orchid children, often remarkable but more sensitive. In his new book, Boyce describes the research about these differences and offers advice on how to help orchid kids. He also shares a painful story from his own family, which he thinks this research has helped him understand. Thomas Boyce is a pediatrician and chief of the division of developmental medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. His new book is “The Orchid And The Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle And How All Can Thrive.”

Well, Tom Boyce, welcome to FRESH AIR. Before we get into the heart of this discussion, I’m going to ask you to kind of address the skepticism that some people might feel at the notion that we can, you know, talk about kids in two categories, you know, orchids and dandelions, in a meaningful way. There might be some skepticism that you can, you know, deal with the complexity of kids and child behavior in that kind of way.

THOMAS BOYCE: You know, well, as a pediatrician and father and now grandfather, I couldn’t agree more. I think it’s very difficult to put kids into categories. And in general, I try to stay away from categories. However, these two categories of sensitivity that’s captured in this metaphor of the orchid and the dandelion suggest a kind of continuum of susceptibility to social environments that, I think, is useful. And certainly within our 30 years of research, those two ends of the spectrum, the orchid child and the dandelion child, had very different patterns of response to naturally occurring adversities.

DAVIES: So there’s some – plenty of scientific data behind some of this. You began as a pediatrician and then became a behavioral scientist – right? – and have done research and have studied a lot of research. You want to just…

BOYCE: Yes.

DAVIES: …Explain these two types, in general, and maybe give us an example?

BOYCE: What we found in our research was that when we began studying the health effects and developmental effects of naturally occurring stressors, that there was a tremendous amount of variation in children’s responsivity in their – the consequences of those exposures to trauma or adversity in their real lives. And that made us realize that we had to pay attention to this. So we began to bring children into very standardized laboratory protocols where we asked them to do a series of mildly challenging tasks. And basically, we found that they varied all over the map.

There were some children who had biological responses to these challenges that were exaggerated. And then there were a large group of children who had almost no biological responses to those challenges. So we began to think of these kids in two different categories. The orchid child is the child who shows great sensitivity and susceptibility to both bad and good environments in which he or she finds herself or himself. And the dandelion child, which really constitute the majority of our children that we have studied, are kids who, like the dandelion, can grow virtually anywhere. They’re relatively unperturbed by the kinds of difficulties and traumas that they encounter.

DAVIES: It was interesting that when you look at health problems with kids, I mean, just the kinds of illnesses kids get – respiratory problems, colds, this kind of thing – that they are unevenly distributed among the population. Is there a correlation between the ordinary or not-so-ordinary physical ailments that kids get and their apparent susceptibility or responses to emotional stress?

BOYCE: Yes, we believe so. We find in our research that the same kinds of patterns of response are found for both physical illnesses, like severe respiratory disease, pneumonia, asthma and so on, as well as for more kind of emotional behavioral outcomes, like anxiety and depression and externalizing kinds of symptoms. So we believe that the same patterns of susceptibility that we find in the orchid child versus the dandelion child work themselves out not only for physical ailments but also for psychosocial and emotional problems.

DAVIES: I wonder if you could just explain one of the tests that you did with young kids to put them through some moderate stress and then measure their responses. Would you just describe how that worked and what it showed?

BOYCE: Yeah. We made an effort to try to understand these individual differences between children in how they respond biologically to mild, common kinds of challenges and stressors. And the way we did that was we brought them into a laboratory setting. We sat them down in front of an examiner, a research assistant that they had not previously met. And we asked them to go through a series of mildly challenging tasks. And these were things like recounting a series of digits that the examiner asked them to say and increasing that from – first – three to four to five digits. Having them just engage in a conversation with this examiner, who might ask them about their birthday or presents or something about their family – that in itself is a challenge for a young child. Putting a drop of lemon juice on the tongue was another kind of challenge that was evocative of these changes in biological response.

DAVIES: And then how did you measure their stress response?

BOYCE: We measured their stress response using the two primary stress response systems in the human brain. And those are the cortisol system, which is centered in the hypothalamus of the brain. This is the system that releases the stress hormone cortisol which has profound effects on both immune function and cardiovascular functioning. And then the second stress response system is the autonomic nervous system or the fight-or-flight system. And this is the one that is responsible for the sweaty palms and little bit of tremulousness, the dilation of the pupils – all of these things that we associate with the fight-or-flight response. So we were monitoring responsivity in both of those systems as the children went through these mildly challenging tasks.

DAVIES: And what differences did you see among the kids?

BOYCE: We found that there were huge differences between children. There were some children at the high end of the spectrum who had dramatic reactivity in both the cortisol system and the fight-or-flight system. And there were other children who had almost no biological response to the challenges that we presented to them.

DAVIES: Right. And so I guess what you’re seeing here is not that these kids were damaged in doing these exercises, but that there might have been something identified, which would make it hard for them later, which might produce more illness or more emotional difficulty later. What’s the link? What’s the explanation about how the neurobiology generates those outcomes, those problems?

BOYCE: Well, we believe – based on what we saw in studying these children at both ends of the spectrum in their real life, we believe that the kids who in the lab looked like high-reactivity children were like orchids. They blossomed and did beautifully and thrived in very positive, supportive, nurturing conditions. But they withered and did profoundly not well in conditions where they were unsupported and where they were threatened within their social environment.

So we found that the orchid children at the high end of this laboratory spectrum had either the best outcomes or the worst outcomes depending upon the kind of environments in which they were being reared. In contrast to that, the children at the other end of the laboratory spectrum, the ones that we called the dandelion children, seemed to do well irrespective of the kinds of environments that they were living in. They did well in highly nurturant conditions just like all children. But they didn’t do so badly in conditions that were more stressful and traumatic as well.

DAVIES: Right. And, you know, I’m interested in why kids who have these intense responses to these minor stresses – that you might see them get sick more. And is the explanation that their bodies essentially work harder to cope with the stress and that that affects the immune system and other functions that make them more vulnerable to illness?

BOYCE: Yeah, the children who fall into the orchid child category had large responses in the functioning of both their fight-or-flight response and their – and the cortisol system. And both of those systems have major effects on immune functioning. And those differences in immune function, we believe, may affect the susceptibility of that child to kinds of pathogens that they encounter in normal life.

So they can alter the child’s ability to build an immune defense against viruses and bacteria that he or she may be exposed to. And they have, also, powerful effects on the cardiovascular system, so could eventually, in adult life, predispose to developing hypertension, high blood pressure, or other kinds of cardiovascular risk.

DAVIES: Dr. Thomas Boyce’s new book is “The Orchid And The Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle And How All Can Thrive.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF RUDY ROYSTON’S “BED BOBBIN'”)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and my guest is Dr. Thomas Boyce. He’s a pediatrician and a professor of development and behavioral health and chief of developmental medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. His new book about some of the differences in children’s responses to stress and adversity is called “The Orchid And The Dandelion.”

You write about your own family. You say you’re a dandelion; your sister, Mary, was an orchid. You want to just describe the two of you and your relationship a bit?

BOYCE: Yeah, my sister Mary was a wonderful child and young woman. She and I grew up very close together. We were a little over two years apart in age. We were very matched in terms of personality and temperament. And we became, in our early years, each the other’s best friend and best playmate.

So for the first 10 or so years of our lives, we were very close, and both of us had the same kinds of experiences within a single family. And yet, over the years, as we entered puberty and adolescence, there began to be a really pretty dramatic divergence in the experiences that I’ve had in my life and those that Mary had in her life.

DAVIES: And how were they different?

BOYCE: Well, my life I think of is a life of almost shameful good fortune. I’ve had a gratifying and productive professional career. I’ve had a stable 45-year marriage to my wife, Jill. We have two thriving children and, now, four grandsons.

And in contrast to that, Mary’s life, I think, would be reasonably characterized as a life of disappointment and affliction. She developed a chronic disease at age 11, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. She carried a diagnosis of schizophrenia by the age of 20. While she was in graduate school, she sustained an accidental pregnancy and delivered a birth-asphyxiated disabled child, and had a life of really ongoing severe mental disorder from that point forward.

DAVIES: We shouldn’t let that little part of the discussion go by without noting that she did some remarkable things, too, things that you really admired.

BOYCE: Oh, she was not only a physically beautiful young woman, but she was brilliant. She got a baccalaureate degree from Stanford University, was a graduate student at Harvard. And yet, all of this kind of fell into her life as she moved along her educational course. But she was a talented, really smart young woman whose life could have been much different than it actually was.

DAVIES: Did your observance of this person that you cared so much about – is that one of the things that drove your interest in child behavior?

BOYCE: Well, it’s an interesting and good question. You know, they say that every photograph is a self-portrait in the sense that the things that we choose to focus on, the frames that we bring to the world that we’re seeing on the outside of ourselves are deeply affected by who we are.

And in retrospect, yes, the kinds of work and research that I chose to focus upon in my professional life as a pediatrician scientist undoubtedly was deeply affected by this experience of having a well-loved sister who diverged so dramatically from my own life course. I have to tell you that I didn’t really realize that until maybe 10 or 15 years ago.

So it was one of these deep currents that was moving and directing my life that I really wasn’t aware of until I began to see how my personal story and my research and career story were really convergent.

DAVIES: So what do we know about where these tendencies come from? How much of it, for example, is genetic?

BOYCE: Well, we have – we believe and we now have the evidence that these two ways of being in the world – the orchid child and the dandelion child – like, virtually all of the traits and characteristics that we carry with us as human beings come from a combination of genetics and environmental influence. There are certainly, and there is evidence now for differences in genetic sequence that, of course, does not change from conception to death that predispose to a child being an orchid child versus a dandelion child.

But we also know that there are influences of early environmental experience. We know, for example, that exposure to adversity and toxic stress early in life – perhaps even in prenatal life – seem to have an influence on a child’s susceptibility to those circumstances, those kind of traumatic experiences later on. So as with many of the kinds of characteristics that we see in individual human beings, it is neither genes nor environments in isolation but a combination of genes and environments that seem to pull for one kind of child versus the other.

DAVIES: Yeah. I have to say one of the fascinating parts of the book was – you’re exploring the ways in which fetuses respond to stimuli in a mother’s womb in ways that will affect these conditions. How do we know, you know, fetuses respond in this way? And what do they respond to in the environment they’re in?

BOYCE: Well, we now know that they respond to a variety of stimuli that they experience during intrauterine life. So we know that babies recognize and respond to their mother’s voice. We know that loud noise and other kinds of auditory stimuli are responded to by a fetus. We also know that the communication – the biological communication between a mom and a fetus via the placenta carries with it exposure to the mom’s biological environment in the form of stress hormones and other regulators that affect the child’s experience in the womb emotionally, physically and so on.

DAVIES: If there are things that can happen when a fetus is in the womb, in utero, which could affect, you know, their susceptibility to stress and other things, I can imagine a lot of parents getting really worried about that. Should they be?

BOYCE: Well, the simple answer is no. If a mom and her partner are living a healthy life, eating good food, avoiding things that we know need to be avoided during pregnancy like alcohol and other recreational sorts of drugs, in all likelihood, that fetus and, eventually, newborn is going to come out just fine. Getting obstetrical care early in a pregnancy is also important. Being taken care of by an obstetrician who can recognize risk factors within that pregnancy is obviously an important piece as well. You know, I think, in general, avoiding the things that are obvious to avoid and doing the things that are obvious to help and allow a child to thrive are the things that will make that pregnancy outcome a good one.

DAVIES: Thomas Boyce’s book is “The Orchid And The Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle And How All Can Thrive.” After a break, he’ll talk about how to help kids who are more sensitive to stress. Also, our book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews a new book about the troubles of Northern Ireland with a kidnapping and murder at the heart of the story. I’m Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF HERBIE HANCOCK’S “MAIDEN VOYAGE”)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Dave Davies in for Terry Gross. My guest is pediatrician and child development researcher Thomas Boyce. His new book explores the differences among children in their sensitivity to stress and adversity. It’s called “The Orchid And The Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle And How All Can Thrive.”

I’m sure a lot of people hear this or read this and think, I’ve got a 2-year-old or I’ve got an infant; have I got an orchid; do I have a dandelion; can I tell? And there is some kind of fascinating stuff in here. There’s this fascinating stuff about differences in inner ear temperature (laughter)…

BOYCE: Yeah.

DAVIES: …That came from studies of monkeys. Is that right?

BOYCE: That’s right. I had the great, good fortune of spending a year on sabbatical at the NIH primate center in Poolesville, Md. And I studied a group of monkeys. We were looking at infection in monkeys who were high and low reactivity. And in order to study infection, I needed to get a temperature on this group of monkeys. And rhesus macaques do not sit still well for either oral or axillary or rectal (laughter) temperatures. But it turns out that these monkeys are routinely anesthetized for veterinarian inspections and so on. So I had a chance to use an infrared ear temperature thermometer in looking at these animals. And I began to find that there were differences between the left and the right tympanic membrane or eardrum temperature.

And we began studying that systematically and found that the more reactive the orchid phenotype monkeys, if you will, had higher temperatures on the right side versus the rest of the monkeys who seemed to have higher temperatures on the left side. So it was a difference that we never knew was even there, that there might be a difference between the left and the right ear. But we think it may have something to do with the blood supply to the two sides of the brain.

DAVIES: So when you looked at kids’ ear temperatures, what did you find?

BOYCE: We had a chance to look at three different groups of human children and found the same kind of phenomenon – that children who had warmer right-sided eardrums were children who were more reactive in the lab and had more of a kind of orchid child profile.

DAVIES: So why might kids who are orchids have a higher stress response, have higher temperatures in their right ears than their left?

BOYCE: Well, we know that there are asymmetries in brain function among all individuals, and we know that children who are predisposed to depression and anxiety kinds of disorders, that in their prefrontal cortex – essentially, the part of the cerebral cortex that lies right behind the forehead – that those children who have these kinds of sensitivities have greater activity in the right side of that prefrontal cortex than they do on the left. Most individuals have higher activity in the left compared to the right. We believe that the reason that we found warmer temperatures in the right ear among children who turned out to be orchid-type children is that the tympanic membrane, the eardrum, on the right side shares the blood supply with the right cerebral prefrontal cortex. So we believe that the eardrum temperature on the right and left side may be a reflection of the degree of actual activity in the two sides of the prefrontal cortex.

DAVIES: You have a chapter here titled No Two Children Are Raised in the Same Family. What do you mean?

BOYCE: Well, really, just that. It’s that the experience of children within a given family – the siblings, if you will, within a family – although they are being reared with the same parents in the same house in the same neighborhood, they actually have quite different kinds of experiences that depend upon the birth order of the child, the gender of the child, to some extent, differences in genetic sequence. It is a way of talking about these dramatic differences that kids from different birth orders and different genders have within a given family. So, for example, my sister and me – we both grew up in the same family. We were attended to and cared for by the same parents. But I suspect that her experience of my family and my experience of that family were considerably different. And there actually is evidence that children from the same family have quite different experiences as they grow up and are reared.

DAVIES: Right. And how do you think that affected the two of you?

BOYCE: Well, I think that my sister Mary was a child that was much more on the orchid end of the spectrum than I was. I was more on the dandelion end of the spectrum. So there were things that happened in our family – conflicts and other kinds of duress – that I think were probably more profoundly affecting Mary than they were affecting me. So basically, who she was as she came into the world set her up to a different sort of experience of our family than my differences from her did.

DAVIES: But in terms of the family environment, I mean, do you think your – I mean, your mom had a different relationship with you than she did with Mary. I mean, in fact, you write a bit about your mom’s history with her parents and how stress can be communicated down through generations. How did that play out in your mom’s relationship with your sister?

BOYCE: Well, my mom grew up in a very competitive, very intellectually intense family – wonderfully so, in many ways. But there was, I think, stiff competition with her sisters. There was a – there were certain kinds of struggles that she had in her own life growing up that I think played themselves out in the way that she cared for her children and, specifically, differences in the way she cared for a female child versus a male child. So whereas I was the firstborn and I was a male child, my sister was second-born and a female child. And I think probably the way that my relationship to my mom evolved was very different from the way that my sister experienced my mom and the relationship with her.

DAVIES: In what way? Did your mom, do you think, in some way, felt competitive with her daughter?

BOYCE: I think there was probably some sense of competition that was left over from her own environment growing up and the competition that she felt with her own sisters. I think that as my sister became ill and began to not have the kind of thriving experience that she had in the first ten years of life, I think that was very challenging to my mom. So I think there were some systematic differences in the way that Mary experienced our family and the way that I did.

DAVIES: You know, we haven’t talked about the end of your sister’s life. And you don’t really reveal that until the very end of the book. I’m wondering why you chose to do it that way. And maybe you should explain what…

BOYCE: Well, my sister Mary ended up taking her own life at age 53 a number of years ago now. It was, as you can imagine, a profoundly sad time for me and for our family, for my brother, for my mom, who was still living at the time. It was a – it was an experience that we didn’t anticipate necessarily. And I – you know, I think the important point about this – the reason that I put it at the end of the book was that I didn’t want the reader as he or she works through the story of the book to have this kind of assumption that an orchid child like my sister was going to devolve into that kind of despair.

I don’t think that the process has ever ended or these children who are especially susceptible. They certainly all will not have the kind of really terrible and sad end that my sister did. And many of them will become talented, gifted, truly remarkable individuals over the course of their life. So although my sister’s life went in a direction eventually that was a sad, tragic end, I know that there were good things that she did with her life. I know that she had much more potential for a very talented and very productive life. She was a good mom. She raised this – her child in ways that were remarkably sensitive and caring.

DAVIES: Dr. Thomas Boyce’s new book is “The Orchid And The Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle And How All Can Thrive.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHICAGO UNDERGROUND QUARTET’S “THREE IN THE MORNING”)

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR, and my guest is Dr. Thomas Boyce. He’s a pediatrician and a professor of developmental and behavioral health and chief of developmental medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. His new book about some of the differences in children’s responses to stress and adversity is called “The Orchid And The Dandelion.”

Raising kids is a daunting, sometimes terrifying thing, right? We have these young lives, and there’s no manual. We have to figure it out. I imagine some parents listening, wondering, is my child more like an orchid or a dandelion? Age 2, can they tell?

BOYCE: Well, they can’t tell in the way that we did because we brought them into a lab. But you’re right. Parenting is a daunting and terrifying job to do. But there are some earmarks of the orchid child that we have identified clinically. And to mention some of those, orchid children tend to be more shy. They’re not always shy, but often they are. Orchid children have this phenomenon of either having the best or the worst outcomes depending upon the kinds of experiences that they have.

They are kids who often withdraw from novel situations. They have a hard time going into experiences that are fresh and new and for them quite challenging. And they have often a variety of sensory sensitivities. An orchid child might, for example, have great reactivity behaviorally to loud sounds, might have taste aversions, might have other kind of sensory sensitivities that are characteristic of that kind of child.

DAVIES: There’s a chapter where you give some practical advice on how to help an orchid child deal with the special sensitivities that they bring. One of them is routine. You say they’re – they might be – have more difficulty with, you know, change. How does that work out day-to-day?

BOYCE: The – this – routines and kind of the sameness, if you will, from day-to-day, week-to-week life I believe is good for all children. And really all of these things that we think of as helpful to an orchid child – none of them is not helpful to a dandelion child, but they seem to be things that are especially beneficial to a child who has this great sensitivity and susceptibility to their environment. So routines is certainly one of them.

Orchid children seem to thrive on having things like dinner every night in the same place at the same time with the same people, having certain kinds of rituals that the family goes through week-to-week, month-to-month. Going to temple, going to church, meeting with the extended family – whatever it is, this kind of routine and sameness of life from day-to-day, week-to-week seems to be something that is helpful to kids with these great susceptibilities.

DAVIES: Right. And there are times of course when we want kids to stretch themselves, and you want to nudge them. And you say that there’s a – the trick is to sort of find out when to nudge and when is – you know, when to protect them from something new and when to push them a little bit. How do we know?

BOYCE: Yeah. I think that this is probably the most difficult parenting task in raising an orchid child. The parent of an orchid child needs to walk this very fine line between, on the one hand, not pushing them into circumstances that are really going to overwhelm them and make them greatly fearful but, on the other hand, not protecting them so much that they don’t have experiences of mastery of these kind of fearful situations. An example that I have used is going to a birthday party with a group of kids that are not all familiar to the child. It may be that that is such a fearful experience for an orchid child that a parent has to make the judgment, look, you really don’t have to go to this if you don’t want to go. But on the other hand, it may be an experience where the parent says, you know, I know you can do this; and I’m going to be there with you; and let’s go and see if we can’t have a good time doing this. So this balancing of a child’s fear with the need for exposure to and mastery of these kind of fearful situations is a challenging task for parents who have an orchid child.

DAVIES: Is there a test, a rule of thumb when you want to back off?

BOYCE: Well, I think it really is just parents’ intuition, Dave. It’s – there is no rule of thumb other than what the parent has learned about that little child over the course of the years that he or she has had with the child. There are, you know, signals that a child may show to really indicate that this is a truly fearful experience. And I think in those circumstances that it’s important for a parent to back off and to say, look, you really don’t have to do this. But on the other hand, I think parents often have good intuitions that a novel situation that is challenging to an orchid child can be done and can be mastered by the child. And that experience of mastery is really an important experience for a child who has these kind of sensitivities.

DAVIES: Well, Tom Boyce, thanks so much for speaking with us.

BOYCE: Well, thank you. I’ve enjoyed it very much. Thank you, Dave.

DAVIES: Thomas Boyce’s book is “The Orchid And The Dandelion: Why Some Children Struggle And How All Can Thrive.” Coming up, Maureen Corrigan reviews a new book about the troubles of Northern Ireland with a kidnapping and murder at the heart of the story. This is FRESH AIR.

Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

Source: https://www.wbur.org/npr/699979387/is-your-child-an-orchid-or-a-dandelion-unlocking-the-science-of-sensitive-kids?fbclid=IwAR3hkg6dIfqke4sUR4aEnmIuSO_4zgwdrH8FKklW3m3rXIkbm7tlX4hqunQ

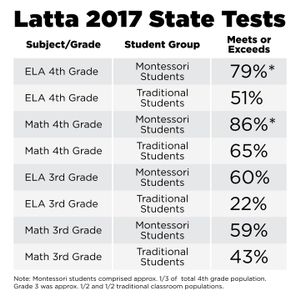

Our Village Montessori

Our Village Montessori About Montessori

About Montessori Calendar

Calendar Blog

Blog Admissions

Admissions Contact

Contact

9(MDAyNzUwMDI2MDEyNTA3MTU5NzcyNTQyNA004))

501.944.4483