The Chemistry Behind Autumn’s Awesome Hues

There are so, so, so many reasons to love autumn (milder weather, jackets, less crowded parks and trails, fewer mosquitos, less poison ivy, cozier camping, pumpkins, squash, gourds… we could go on forever), but the best—and certainly brightest—may be what happens to the leaves.

But what exactly does happen to them? Sure, they change from green to yellow and orange and red and even purple and magenta, but why? What’s going on within them that causes this celebrated transformation?

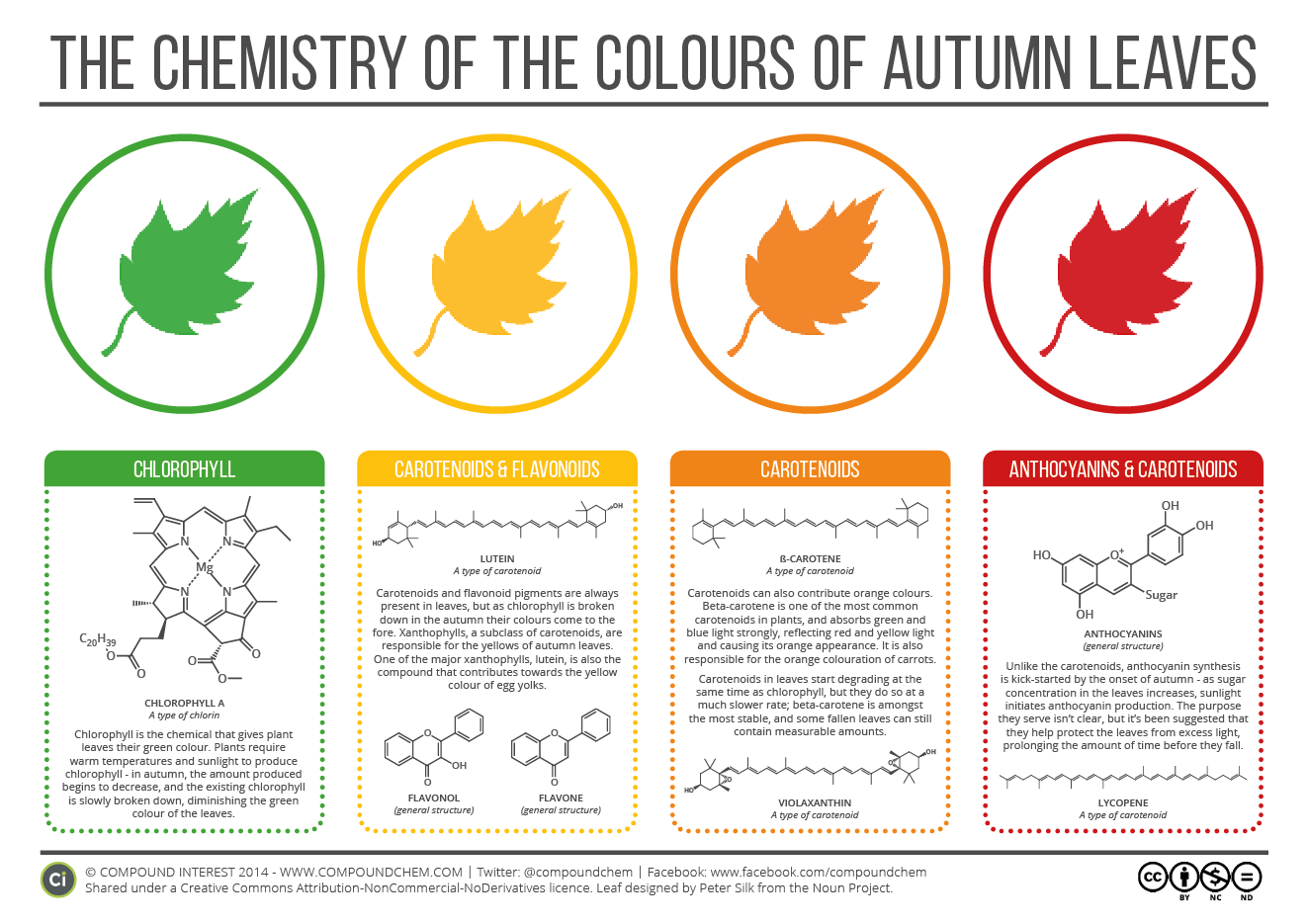

Wonder no more, because Compound Interest, an educational website run by UK-based chemistry teacher Andy Brunning, has created an eye-pleasing one-page graphic that plainly explains the chemicals responsible for autumn’s dazzling leaf show.

Basically what’s going on is that flavonoids and carotenoids, the compounds responsible for fall foliage’s yellow and orange-red hues respectively, are present in leaves throughout the year, but they’re overwhelmed by high levels of vivid green chlorophyll during the summer months. Leaves can only produce chlorophyll—a necessary component of photosynthesis—in the presence of warmth and sunshine, which of course become increasingly scarce starting in late September. As chlorophyll production slows and then stops, yellow and orange flavonoids and carotenoids are allowed to shine through.

Beyond fall’s fiery hues, carotenoids are responsible for the salient shades of many foods including carrots, egg yolks, and tomatoes.

Autumn’s deepest reds, purples, and magentas are caused by anthocyanins, a type of flavonoid that unlike those discussed above is not present throughout the year. Its production is triggered only in the fall when sunlight interacts with seasonally higher concentrations of sugar in the leaves.

Head to Compound Interest to further increase the depth of your leaf-peeping knowledge.

Our Village Montessori

Our Village Montessori About Montessori

About Montessori Calendar

Calendar Blog

Blog Admissions

Admissions Contact

Contact

501.944.4483